Across the street Terminal Annex was a federal building purposed for a post office and mail processing center but is no longer publicly accessible. This blog post explores the earlier community "north of Macy Street" from about 1828 long before the arrival of Terminal Annex.

The footprint of the future post office will be covered - where Date and Ogier Streets once were - the crossroads of L.A. from the time it was a Spanish pueblo, to a Mexican ciudad and towards a settling-in period as an American city. Other areas to be analyzed are roughly bound by North Main on the west, Alhambra Avenue on the north and the L.A. River on the east.

Gilbert Stanley Underwood designed the building that stands near the corner of Alameda Street and Cesar E. Chavez Avenue (name changed from Macy Street in 1994). Construction began in 1939, expanded and altered several times into the 1970s and operated until 1989 when a larger facility was built in south L.A. Underwood applied elegant details to numerous federal and rail projects nationwide, including train stations like the neglected East Los Angeles Train Station and the former Ahwanee Hotel at Yosemite National Park, California.

Macy Street originated after 1851 with the arrival of Massachusetts-born Dr. Obediah Macy with family in tow following their overland journey. He bought the Bella Union hotel, and he opened the Alameda Baths before passing away in 1857.

One could consider Terminal Annex as part of the southernmost, "Civic Support" portion of the North Industrial District or Dogtown, covered on Eric Brightwell's blog.

The proximity of this neighborhood to downtown made it a vulnerable target for change by city planners, impacting residents of modest or limited means. As Brightwell points out, acres of residences were cleared out in Dogtown about 1941-1942 and a city public housing project - the William Mead garden apartments - was built and continues to exist today. Brightwell writes about a continued loss of homes in Dogtown during the early 1950s with authorities citing crime, delinquency among youth and disease as the impetus to clear everything out.

|

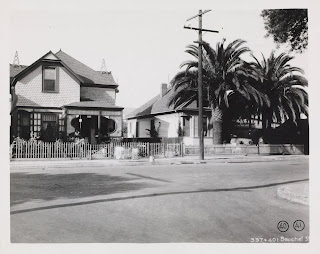

| Homes at 337 and 401 Bauchet Street, ca. 1930s (Photo added 6.27.2021. Courtesy Pacific Rim, Huntington Digital Library) |

Terminal Annex and the concurrent development of Union Station, with its supporting infrastructure, all led to the gradual obliteration of the residential places north of Macy. Development chipped away this area while at the same time Old Chinatown was dismantled for the train station. In the 1950s the residents at Elysian Park's Chavez Ravine were pushed out, but in the next two decades more blocks north of Macy would go away. For an in-depth historical read on the racial and political reasons that led to the removal of primarily the Mexican (and Chinese) from these parts, consult The Los Angeles Plaza, a Sacred and Contested Space, by William D. Estrada, 2008.

Lumber Yards and an Orphanage

An historic map dates the Jackson, Kerckhoff & Cuzner lumber yard as early as 1881 at the spot of the future post office. There were other lumber businesses nearby. South of Macy Street was the orphan asylum started by the Sisters of Charity in 1856 on property bought from Benjamin Wilson (he being an emigrant from Tennessee in 1841.)

The area along Macy, included with the greater North Industrial District, comprised parts the Eighth Ward, a voter district of the city. Within the Ward the areas were divided into four precincts, A through D. During elections after 1889, the polling place for precinct B was Kerckhoff & Cuzner's office (the business name, Jackson, had been dropped off by then.) A son of French pioneer Louis Bauchet served as a judge of the precinct - more on the family below.

|

Dakin's Tract Maps of Los Angeles, Volume 1, 1888

(Courtesy of the Seaver Center)

|

Fruit, Wine, Vineyards, Gardens and a Lover's Lane

Louis Bauchet

Those who lived here north of Macy Street are recorded in part by extant street names and more names uncovered on historic maps. Bauchet Street is still prominent, after the area underwent many configurations including removal of streets and the redesigns of existing streets. Louis (or Luis) Bauchet (or Bouchette or Bochett) owned chunks of land north of Macy and east of Alameda. Thomas Pinney (A History of Wine in America, 1989) wrote that Bauchet was "a cooper by trade and a veteran of the Napoleonic wars, came to California in

Louis Bauchet established a vineyard a little earlier than the another Frenchman, the well-known Jean-Louis Vignes - when Vignes arrived, he met several French settlers, including Bauchet. They both appeared in Los Angeles' first census of 1836.

Bauchet wed to Maria Basilia Alanis, a Californio and granddaughter of a Soldado de Cuera of 1781, Maximo Alanis - he was one of the Spanish soldiers on the expedition leading the Los Angeles Pobladores to Mission San Gabriel.

Bauchet married into an elite family. (Scotsman Hugo Reid wrote about the social affairs - dinners with Abel Stearns and his wife Arcadia Bandini de Stearns followed by dancing across the street at the ballroom of Doña Basilia, where large dances were always given.) This was in the 1840s when the Bauchet adobe was on Calle Principal. She died of old age in 1889 at her residence on Date Street.

In the period before a war was ignited by President James Polk, grape-growing was an active industry in Mexican Los Angeles. From north of Macy Street one could peer south towards Aliso Street at Vignes' property, the Domingo vineyard and nearby Mateo Keller's vineyard, too. It is not too far-fetched to imagine the bucolic scenery measuring up to present-day Temecula Valley.

North of Macy became home to European immigrants and American settlers, after the war - in 1849 and in the decade of 1850 after California was admitted to the United States. The gardens nourished by new settlers in the dusty, new American city are profiled in the 2003 book Tangible Memories: Californians and Their Gardens, 1800-1950 by Judith M. Taylor & Harry M. Butterfield.

Leonce Hoover

Swiss doctor Leonce Hoover arrived in 1849 after serving as a surgeon to Napoleon Bonaparte's army. He too started a vineyard, and his home was noted for its beautiful gardens and plantings. Members of the California State Agricultural Society visited the area in 1858 and were so impressed by Hoover's property that a complementary write-up appeared in the Society's report. (The Society observed that Dr. Hoover drank "the juice of the grape" all day long.) His son Vincent became a businessman, land developer and served on the Common Council (city council of the time.)

|

| Vignette from an 1857 map by Kuchel and Dresel (Courtesy of the Huntington Digital Library) |

Thomas J. White

Another settler in the 1850s was from St. Louis. White was the first Speaker of the state's Assembly in 1849 at San Jose, California. He bought 50 acres north of Leonce Hoover's property. In 1857 he served as vice-president of the State Agricultural Society. The Society's 1858 report said this about his property: "In 1858 he was growing nine varieties of figs, white sapote, avocado, mango, tamarind, lemon, lime and orange." "Picture Dr. White's old garden: the dwelling is situated about five hundred yards from the street and approached by a drive bordered by English walnuts and luxurious pomegranates to within a hundred feet of the house where it branches and encloses an oval containing a large fountain, ornamented with sea shells, coral, evergreens, and flowers."

I.S.K. Ogier

Nearby at Macy and Date Streets was the six-acre property and home of Judge Isaac Stockton Keith Ogier and his second wife, Anna. They had at least two Indian servants. The style of his house was a departure from the architecture of the former Mexican city. His two-story adobe had a faux blue stone façade. A fountain was set in the front with well-placed shrubs. The visiting State Agricultural Society wrote "The lady of the mansion appears as much home in her garden as His Honor on the bench of the United States District Court." More on the importance of Judge Ogier to follow below.

Lovers Lane

The L.A. City Archives has preserved an 1871 map of a long thoroughfare called "Lovers Lane", drawn by the county surveyor, William P. Reynolds. Glen Creason, map expert at the Central Library, suggested in his 2010 book, Los Angeles in Maps, that the road had been re-named to Date Street in 1877. This is the same Date Street that once ran at about a 45 degree angle beginning at Macy Street.

Garibaldi Hall was located at 746 Date Street, the meeting place for Italian Unione Frattelianza Garibaldina Society. The Bauchet children sold a lot to the organization in 1888 for $2,000.

|

Baist's Real Estate Atlas, 1921

(Courtesy of the Seaver Center)

|

The First Judge for the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California

A significant historical aspect at this place, north of Macy, under Terminal Annex, was the spot in the newly American place chosen by Isaac S.K. Ogier to regard as his home. He was born 1819 in Charleston, South Carolina, where his English-born father and French-born grandfather both lived and died. Charleston contains a street called Ogier. Ogier ancestors were Huguenots. Judge Ogier's father owned nine slaves, as listed in the 1830 census.

He moved to New Orleans to practice law. While there he enlisted and served twice in the Louisiana infantry during the war with Mexico. The Gold Rush turned him into a Forty-Niner. He was a widower, got on a ship and left behind a young daughter to get to California.

He stayed in northern California briefly, and became a member of California's first Assembly, representing San Joaquin. A bill he introduced to bar the admittance of free Blacks to California failed to pass. Ogier arrived in Los Angeles about 1851 and in 1854 was appointed Judge of the federal court for the southern district of the California.

He never lost his gold fever - when southern California's big gold strike occurred in 1861 at Holcomb Valley, San Bernardino, he secured an Ogier mine. He was visiting the mine in May of 1861 when he died of apoplexy - a month after the start of the American Civil War.

He moved to New Orleans to practice law. While there he enlisted and served twice in the Louisiana infantry during the war with Mexico. The Gold Rush turned him into a Forty-Niner. He was a widower, got on a ship and left behind a young daughter to get to California.

He stayed in northern California briefly, and became a member of California's first Assembly, representing San Joaquin. A bill he introduced to bar the admittance of free Blacks to California failed to pass. Ogier arrived in Los Angeles about 1851 and in 1854 was appointed Judge of the federal court for the southern district of the California.

He never lost his gold fever - when southern California's big gold strike occurred in 1861 at Holcomb Valley, San Bernardino, he secured an Ogier mine. He was visiting the mine in May of 1861 when he died of apoplexy - a month after the start of the American Civil War.

Court historian and former judge of the southern district himself, George Cosgrave, provided a lively account of Ogier's life, his journey and career in Early California Justice, the History of the United States District Court, 1948. Prior to becoming a judge, in 1851 he partnered with a Spanish-speaking Peruvian attorney, Manuel Clemente Rojo, so as to drum up clients of land claim disputes and petitions. He also served briefly as U.S. district attorney for the southern district in 1853. During his brief capacity as district attorney, a noteworthy dispute that Ogier investigated involved the state foreign miners' tax. American miners had a quarrel with Mexican miners in Mariposa. Historian Cosgrave wrote that Ogier reported accurately and without bias that the Americans' dispute was baseless.

Since the Bay area was included in the southern district, Ogier was the presiding judge for some of the first cases for Mexican grants: he ruled in favor of the petitioners of grants encompassing today's Oakland and Alameda County.

Cosgrave and others have written about Ogier's role (and his unconventional manner) in the adjudication of land rights and rancho claims, particularly to conform with the 1848 war treaty, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The treaty, in simplest terms, afforded Californios the right to retain their land.

A major appeal heard by Judge Ogier was Antonio Maria Lugo's 29,500-acre Rancho San Antonio. (Claimants had the right to appeal any delays or denials and be heard by the U.S. District Court.) Lugo's heirs thankfully received a land patent. Historian Paul Gates, in Land and Law in California, 1991, argued that Ogier was "reputed to be more lenient than the northern district judge, Ogden Hoffman, so the success of Los Angeles claimants may be a reflection of judicial preference as well."

On the bench he was unorthodox. He rarely wrote legal opinions to support his decisions, lacking citations of authority. However, Cosgrave drew an instance that exemplified Ogier's sense of duty and high regard for the integrity of the court: Pacificus Ord, as a U.S. district attorney, failed to object to a land claim. Ogier found out soon that Ord himself had interest in the particular piece of land and therefore was operating unethically - the land claim was never confirmed.

He was active in the L.A. community - he was a part of a committee to form a Protestant society in 1859 that lead to the establishment of the first Protestant church which he did not live to see in 1864. He was also a member of the semi-vigilante, semi-social citizen crime enforcement group, the Rangers, to help curb the rampant lawlessness.

|

| Baist's Real Estate Atlas, 1921 Date & Ogier Streets represented crossroads in L.A. history beginning with the era as a Spanish pueblo in Alta California (Courtesy of the Seaver Center) |

The Sepulveda Family

Also visible in the above, larger 1921 map is the Sepulveda Vineyard Tract (where today's county jail complex stands.) One of the Sepulveda families (descendants of a Spanish Mexican soldier who served in Alta California), namely Jose Dolores Sepulveda, his wife Louisa Domingo Sepulveda and one of their children, Plutarco, were listed at 726 Date Street as found in city directories beginning in 1895. Their home was right at the T intersection of Date & Ogier. There is some irony that the Sepulveda house was located probably right at the entrance gate of the Ogier house, the judge who dispensed decisions on the lands of the Californios. (In one newspaper, the address was also cited as 307 Ogier, which was an adjacent house on the lot.)

|

| Louisa Domingo Sepulveda with her child, n.d. (Courtesy of the Seaver Center) |

|

| Jose Dolores Sepulveda, ca. 1860s (Courtesy of the Seaver Center) |

|

| Reymunda Feliz de Domingo de Romero with son J.A. Domingo (Courtesy of the Seaver Center) |

The Los Angeles Times reporting on her death wrote that 50 years earlier, Reymunda "was rated the wealthiest woman in the southern part of the State and her home [on Aliso Street] was the center of cultured and aristocratic society." "Señora Romero was the lady bountiful of the pueblo, and day after day used to make the rounds of the neighboring ranches, distributing provisions and delicacies and spreading cheerfulness as she went."

Religious Diversity & Tolerance

The Sisters of Charity formed a Catholic orphanage by 1856. Probably perpetually cash-strapped, the sisters instituted a fundraising festival in 1858 whereby the ladies of the community could contribute food and handmade items to be sold. Two of the women, Mrs. Thomas J. White and Louisa Hayes Griffin helped to spearhead the event, that brought together women from diverse denominations for the sake of charitable giving, including Jews and Protestants. Historian Kristine Ashton Gunnell pointed out that "even Anna Ogier, who privately expressed anti-Catholic sentiments, donated items and may have taken a turn at the sale table." The three women were the wives of prominent men in the community, and Mrs. White and Mrs. Ogier lived north of Macy.

A Public School and a Library

At the end of Ogier Street, where Macy and Avila Streets once intersected, a public school and library were proposed in 1894 to be located in the Mead Tract. The New Macy Street School and library show up next to each other on the 1921 Baist map shown above. (Mead was the same real estate developer associated with the William Mead Homes mentioned above in Dogtown. He died in 1927.)

The school was the subject of a health crisis in its history. In 1906, the Macy Branch Library was only one of eight branch libraries in the City system.

The Slaughterhouse

Further east along Macy - 808 E. Macy Street - along the river was a slaughterhouse that the City approved after a lengthy deliberation. This site was the former home and garden of Leonce Hoover.

Cudahy Packing Company petitioned the city council in December, 1892, informing of their capacity for 500 hogs and 50 cattle a day, with employment for 400 men.

In 1904 a major fire destroyed much of the plant, at which time residents protested against having the business resurrected. The company re-built, and Cudahy was still listed in the 1956 street directory.